Image: Woman reading a book. Photo by Lucia Parillo via pixabay.com.

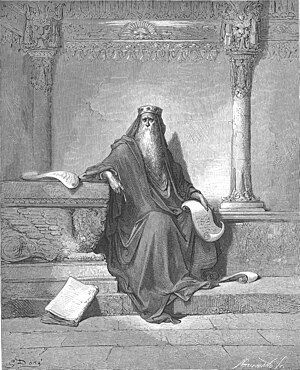

The tradition teaches that Solomon is the author of three books of the Bible. The first is the book Shir haShirim [Song of Songs] a love song written when he was a young man. The second one, Mishlei [Proverbs] was supposedly the product of middle age. The third is Qohelet [Ecclesiastes] which he wrote as an old man who had become cynical. As a description of the contents, it works. In fact, all three books were likely written or assembled long after Solomon’s death. We know this because there is Aramaic in each, and that language did not come into use among Jews until after the Babylonian Exile in the sixth century BCE.

Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes are read for Passover and Sukkot, respectively, but Proverbs does not have a fixed use in the Jewish calendar. The most famous part of the book is Eshet Chayil [Woman of Valor], Proverbs 31: 10-31, which is read or sung in some Jewish homes on Shabbat evening.

A capable wife who can find?

She is far more precious than jewels.

The heart of her husband trusts in her,

and he will have no lack of gain.

She does him good, and not harm,

all the days of her life.

She seeks wool and flax,

and works with willing hands.

She is like the ships of the merchant,

she brings her food from far away.

She rises while it is still night

and provides food for her household

and tasks for her servant-girls.

She considers a field and buys it;

with the fruit of her hands she plants a vineyard.

She girds herself with strength,

and makes her arms strong.

She perceives that her merchandise is profitable.

Her lamp does not go out at night.

She puts her hands to the distaff,

and her hands hold the spindle.

She opens her hand to the poor,

and reaches out her hands to the needy.

She is not afraid for her household when it snows,

for all her household are clothed in crimson.

She makes herself coverings;

her clothing is fine linen and purple.

Her husband is known in the city gates,

taking his seat among the elders of the land.

She makes linen garments and sells them;

she supplies the merchant with sashes.

Strength and dignity are her clothing,

and she laughs at the time to come.

She opens her mouth with wisdom,

and the teaching of kindness is on her tongue.

She looks well to the ways of her household,

and does not eat the bread of idleness.

Her children rise up and call her happy;

her husband too, and he praises her:

“Many women have done excellently,

but you surpass them all.”

Charm is deceitful, and beauty is vain,

but a woman who fears the Lord is to be praised.

Give her a share in the fruit of her hands,

and let her works praise her in the city gates.